[based on Dr. Yo’s original post from March 2019]

For nearly half a century, I have regularly hosted lively debates in my head about which side of the intelligence spectrum standardized tests reward more: students on the natural, seemingly intuitive smarts side or those whose intelligence derives from knowledge and skills acquired through education. Or to frame it slightly differently, do standardized tests ultimately reward kids who grow up reading and playing with numbers by natural propensity and choice or are otherwise “gifted” in verbal/linguistic and mathematical/logical intelligences, or can students compensate for what they may lack in neural/cognitive firepower with commensurate determination and discipline to learn how to compete with or even outperform such students in head-to-had combat with #2 pencils and bubble sheets.

As both a high school classroom teacher across the curriculum for two decades and a test prep coach and college advisor for three, I feel uniquely positioned to entertain various perspectives and arguments on both sides and have vacillated in my “final” disposition on the matter more times than I’m comfortable admitting in public. Currently, I’m of the mind that the answer to the question is analogous to the answer to the classic academic debate about which its more important to the development of human personality, values, and abilities: nature or nurture?

My first memories of standardized tests date back to elementary school, when we were tracked into reading group levels based on popular public and private school reading comprehension assessments at the time developed by the Chicago-based Science Research Associates. Teachers spoke of “SRA,” an acronym whose meaning I only discovered moments ago, which referred to the colored-coded cards and questions housed in an imposing plastic bin that always seemed to make scary faces at me when the teacher wasn’t looking. The three letters still set vestigial butterflies aflight in my stomach. I hated reading comprehension tests because they always seemed to get the better of me: I had a hard time quieting the chorus of voices and doubts and distractions in my head, largely based on fear surrounding the high stakes consequences of my performance (at least to my third-grade mind), so I often couldn’t even get the gist of a paragraph, and I found the questions confusing and mysterious, seemingly scribed in a code whose cipher came factory installed only in the so-called naturally gifted students. Supported by a culture that still widely believed such tests of English and mathematical “aptitude” measured congenital intelligence, and still largely supported by the wider scientific community that believed intelligence is bestowed at birth, a feature of your particular brain, and remains essentially static throughout life. Until the 1980s, no one studied for the SAT or ACT for the same reason no one studied for an IQ test: it would be a waste of time since intelligence/IQ is a quantifiable genetic trait and, like height and eye color, you get what you get at birth, or even conception. By third grade I believed the SRA assessments told me with all the authority of the entire grown-up world that I was just so smart and no smarter. Reading Group Level 2.

It wasn’t until junior year of high school that my own lived experience began to change my thinking about the subject. Up to that point, I had excelled in the elementary and junior high school classrooms—as measured by teacher comments, report cards, and grades—but the results of every standardized test told a different story that I was just “above average.” When in early high school I set my sights on attending a selective liberal arts college with dreams of the Ivy League, junior year marked the biggest crossroads of my academic career, when I’d either have to find a way to solve the great enigma of standardized tests, especially the terrifying SAT, or remain a Reading Group 2 student at least through college.

Fortunately, based largely on Howard Gardner’s work on Multiple Intelligences and a slowly changing, now widely accepted, scientific model of the brain that changes over time (today there are whole undergraduate and graduate departments devoted to studying the many facets of Neural Plasticity, which is wholly dedicated to developing this model, something literally unheard of in my parents’ generation), new opportunities and hope was proferred to students like me. So whereas my mother tells the story of how her parents, like most others at that time, adamantly maintained studying for aptitude/IQ tests like the SAT was a waste of time and resources (if not downright cheating), and whereas Stanley Kaplan, Princeton Review, and the multi-billion dollar test-prep cottage industry of tutors and organizations were all yet to be born, she and everyone she knew took the test cold.

By the early 80s, there were a few options for what history can now label rudimentary attempts at standardized test prep, forged by creative and forward-thinking educators who fought an uphill battle against a majority of old-school naysayers who obstinately stuck to the conventional “wisdom” that test prep doesn’t help. (A fascinating part of this history is the College Board’s tactic admission, to its chagrin, that indeed the SAT is not an intelligence or IQ test at all when it quietly and temporarily changed the meaning of SAT from Scholastic Aptitude Test to Scholastic Assessment Test—which was at least a more accurate descriptor of the contents of the exam according to most educators who studied it—and finally to nothing at all; that is, today the SAT doesn’t stand for anything but is still called the SAT simply for cultural continuity since most people know what the test is by that name. As indicated in the industry joke that the SAT is not a good measure of college readiness but rather is a good measure only of how well you’ll do on the SAT, I find that the SAT’s not signifying anything is the College Board’s most accurate descriptor to date. LOL).

Thankfully, my very educationally progressive parents wanted to give me every opportunity to reach my SAT goals (we East coast students had no idea yet of the existence of the ACT that midwest and southern US students had been taking for years as their entrance exam, and vice versa): I figured based on conversations with my guidance counselor and comparing notes with older friends applying to selective colleges the year and two ahead of me (yeah, Naviance and Google college profile searches were also beautiful things of the distant future) that I needed to go up at least 200 points between the PSAT in October and the SAT that would count for college admissions in May of my junior year (there was no “Score Choice” in the olden days, so while the PSAT, like today, didn’t officially count toward admissions, every SAT that students took and had a window of just 24 hours to cancel if they got sick in the middle or otherwise knew they had a really bad performance, were automatically sent to college). Most people, including educators, believed engaging a tutor or enrolling in a class would not provide a strong enough prescription for the desired remedy, but off I went once a week for months, powered more by hope than evidence, to Mrs. Clarine Coffin Grenfell, the beloved English department chair at Hall High School for many years, who had recently retired from the classroom to pursue a business teaching Evelyn Woods speed-reading and preparing students for the SAT without the benefit of Khan Academy, access to actual exams, or even test prep materials that students today take for granted. I was on a mission to achieve my goal, even though all my prior standardized test experience kept the doubting voices in my head alive and well throughout the process, and I religiously carved out 30-60 minutes every day from mid-December to early May to study. When the envelope came from the College Board at the end of May (right, no internet or World Wide Web yet), I still remember how much my hands shook as a tried to rip it open. To my amazement and delight, I had gone up well over 200 points and for the first time in my entire life earned a standardized test score that corroborated my academic performance in the classroom. That moment changed my whole self-narrative, instantly reforming my inherited thinking about standardized tests and static brains and intelligence measures, helped me get into my top choice colleges, planted a seed for my future career work, and, indeed, changed my life.

In an ideal world, college entrance exams would obviously identify students most likely to excel in college, rewarding those who really “get” and revel in English and math and other academic disciplines, those who truly appreciate the craftspersonship of writing or the elegance of numbers or the utility of science or the often inscrutable but powerful social forces embodied in and unleashed by the multiplicity of human cultures, who are most likely to thrive in their academic pursuits in college and have the best chances for contributing to knowledge in graduate school, the Holy Grail of higher education.

As a vocal critic of many aspects of standardized testing as a measure of college readiness, I have to admit, somewhat begrudgingly after 30 years coaching and observing students, that while imperfect and often mis-categorizing promising college scholars with low scores, both exams do a decent job—my own daughter is a prime example of an exception, as her SAT score was mediocre (largely because she made a conscious choice to spend the time she knew it would take to raise them in academic and extracurricular pursuits that were far more meaningful to her), but she earned straight A‘s and A+‘s, and more of the former than the latter, in eight consecutive semesters in one of the country’s top undergraduate psychology programs. Many students at both ends of the spectrum, those “naturally’ gifted and those who are coached and rely on acquired knowledge and skills, earn top scores on both tests every time they’re given. But among students who don’t prepare, or those who prepare very little, I have seen time and again that the same students who consistently earn good grades in English and math classes because of their natural proclivitiies for those subjects can answer the most challenging standardized test questions that trip of the majority of other students.

Having admitted that, there are many instances where acquired knowledge trumps natural intelligence. To take just one example from the way both the SAT and ACT measure language proficiency— the SAT’s Writing and Language section and the ACT’s English test are almost identical in both form and content. In theory, the tests are designed to measure language proficiency developed over years of reading, speaking, and studying the syntax and grammar of the English language throughout primary and secondary schooling. Many of these students know when a sentence just doesn’t “sound right” because of their prior, richer experience of language than less bookish students. They therefore seem to intuit correct answers, sometimes without even knowing which particular grammatical rule was broken (perhaps analogous to musicians who can play by ear as opposed to those who play only from written music). This ability to “think on your feet” based on what you already know from past experience is a valuable resource on college entrance exams and I don’t think anyone feels that rewarding such students with high scores is unjust.

But students who study the specific bodies of material that come up on every SAT and ACT rather than rely on their naturally or organically developed intelligence also have a valuable resource and are sometimes better positioned to get questions right than their naturally gifted counterparts. The truth is, neither test measures proficiency in English per se, but rather their proficiency in an academically defined subset of our language called “Standard Written English.” Unlike music and other art forms, there are ironclad rules of formal English that, when learned, lead to right answers. I like to say that knowledge of the rules and conventions of Standard Written English serve to “mathematize” English in that, as tested on the SAT and ACT, English language follows black-and-white, cut-and-dried rules that yield right and wrong answers as much as the problem-solving techniques of math always converge to a single correct answer. But of course it doesn’t.

Professional writers often break the rules of formal English grammar and, frankly, they don’t give a damn: if professional writers have to choose between a grammatically correct expression and one that is ungrammatical according to conventional rules but is more expressive of the ideas in their heads, they will opt to break the rules every time. Wiston Churchill made this point cogently and humorously when he famously replied to a critic who was apparently appalled he had ended a sentence with a proposition (that’s a big no-no in Standard Written English), he is said to have retorted, “Madame, that is the type of nonsense up with which I shall not put,” demonstrating that occasionally conventional rules get in the way of clear expression, which is always a writer’s or orator’s ultimate goal.

A specific example of such a rule honored and tested by both the SAT and ACT is the interdiction against “comma splices.” Standard Written English says that it’s always wrong to separate two independent clauses (basically, two stand-alone sentences) with a comma. You cannot write, “We went to the store, we bought eggs.” That’s a comma splice. Rather, a writer must separate the two independent clauses with a coordinating or subordinating conjunction (“We went to the store, and we bought egg” or “We went to the store, where we bought eggs”), a semicolon (“We went to the store; we bought eggs”), or a period ( “We went to the store. We bought eggs.”) The student who has read widely and deeply for years will have encountered many instances of professional writers’ use of comma splices and may not find it wrong when they see it on a test. But the student who has studied the rule about comma splices will easily eliminate a potentially seductive but always wrong answer choice.

So what ultimately yields the highest scores on today’s college entrance exams, natural intelligence or learned intelligence? BOTH, but ties go to those who become students of the exam and study as hard and long as necessary to master the peculiar and historically inherited knowledge and skills today’s exams value.

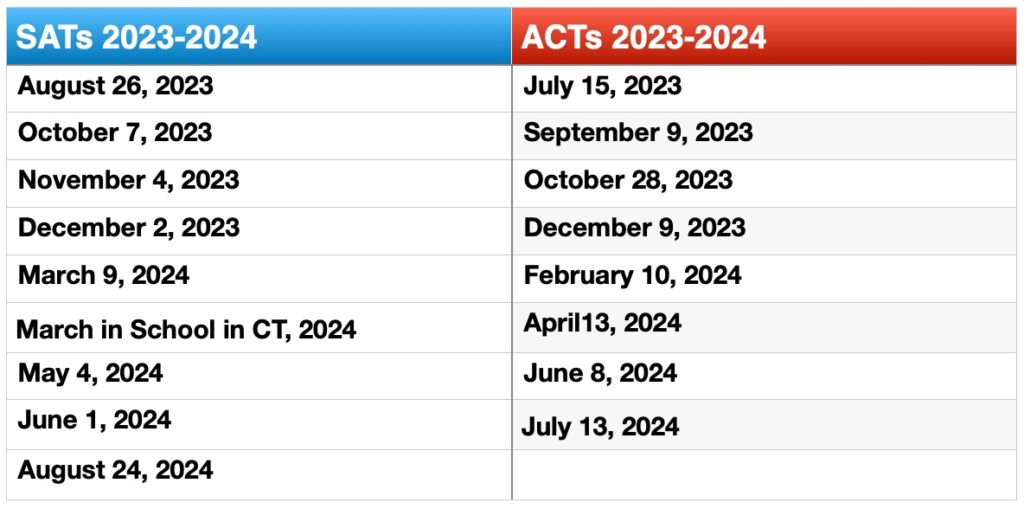

Check out CPE’s 4 small classes for every SAT and ACT given throughout the year